Notes About Tree Blindness

What exactly is “tree blindness” you ask? Well, its the natural tendency for people these days to not be able to identify different tree species. But don’t fret, I will show you a couple of the most important and widespread trees this side of the Mississippi! I learned a lot by trying to figure out what some of these trees were, and I struggled with differentiating different trees. Below is a list of my tree blind struggles!

Before this class I used to always associate the thorns of a honeylocust with its cousin the black locust…oops!

On my adventures I had a hard time trying to figure out the difference between red and white mulberry trees. (It’s all about the drupes!)

Is it an American Elm or an American Hornbeam…elms have fatter leaves, hornbeams have thinner and longer ones.

Sugar, silver, red maple, which is it??!!??! The lobes and ends give it away.

Red oak or white oak, look for the bristles to determine your path!

Now on to Trees!

I found all of these trees in Scioto Grove Metro Park on the southside of Columbus between Grove City and Obetz, and about a 5 minute drive from my house (please don’t stalk me). All of these are in riparian areas, bottomlands, and uplands right next to the Scioto River.

Honeylocust – Gleditsia triacanthos L.

I found this near the edge of a riverbank, farther back but still subject to possible flooding.

Perhaps one of the most recognizeable trees of eastern North America once you know what it is! This tree is most noticeable by its masses of thorns peppered along the bark but can also be identified by the alternate, pinnately compound, somewhat long serrated leaves as pictured below.

Leaves of the honey locust are pictured here. I would have snapped a better shot but most were little babies and I’m too much of a tree hugger to pick off these little guys.

The formidable bark of the honey locust.

Native Americans would use the pulp of the seed pod as a sweetening agent for foods, the wood for bows, and the thorns as pins for sewing. (https://plants.ces.ncsu.edu/plants/gleditsia-triacanthos/)

White Mulberry – Morus alba L.

I found this in a transitory zone from uplands to bottomlands, also near a forest edge into prairie. Another individual was found in bottomlands along the forest edge into floodplains.

The leaves of this tree are alternate, simple, coarsely serrated, and oval to nearly circular. They may be lobed or unlobed. The white mulberry can easily be confused with its cousin the red mulberry (Morus rubra L.) but is distinguishable by the larger serrated teeth and by its fruit (a drupe technically), which grow in clusters rather than solitary drupes. The bark of the tree may have a yellowish tinge and the leaves are smaller compared to the red mulberry.

A twig of the white mulberry, with immature clusters of drupes.

The white mulberry tree has been naturalized in North America after introduction by colonists from eastern Asia. This was due to belief that a silkworm industry would take off here, as the leaves of the mulberry are the chief food of silkworms, but due to standards of living here it was economically infeasible. (From our Trees book by William Harlow)

Sugar Maple – Acer saccharum Marsh.

Found in an uplands region overlooking floodplains and riparian forestland.

The sugar maple is probably the most common maple in North America. The leaves are opposite, simple, 5-lobed which are usually shallow, and have U-shaped winged fruits.

The leaf of a sugar maple.

The young tree in the middle is the sugar maple. The bark is noticeably gray-er than surrounding trees.

The sugar maple is the go-to tree for maple syrup! French settlers were taught how to extract the pancake essential from Native Americans. The wood ash from this tree was used in pioneer soapmaking. (Harlow)

Hackberry – Celtis occidentalis L.

Found very close to the sugar maple, also in an uplands region on a forest edge.

The leaves of this tree are alternate, simple, lance-shaped, serrated, and with an unequal heart-shaped base. Looks very similar to the American Elm, but can be distinguished by its web-like veins over the elm’s parallel ones. The bark is also quite warty!

The leaf of a hackberry tree.

The warty trunk of a hackberry tree.

While of little importance for timber, the fruit of the hackberry tree is prized by nearly 25 different bird species. The fruit is also noted to have a datelike taste. (Harlow)

Sycamore – Platanus occidentalis L.

Found almost touching the water of the Scioto. On a riverbank as close to the edge as possible. Other sycamores were in the water and doing great.

The leaves of a sycamore are alternate, simple, resembling maple leaves but with very coarse teeth. The tree is most recognizable by the upper portion of the tree, which loses its rough bark and is replaced by smooth, gray or white bark.

Sycamores are some of the largest trees in eastern forests.

I was unable to find leaves near the ground but these trees are easy to spot once big like this!

The wood of the sycamore has been used by early settlers for canoes, and as butcher blocks due to its toughness! (Harlow)

Eastern Cottonwood – Populus Deltoides Marsh.

Uplands region but close to riverbank. Found along a forest edge.

Eastern cottonwoods have leaves which are alternate, simple, triangular in shape, and which quiver like aspen leaves in the wind. The fruits of this tree are bunched like a string of beads and release wispy, cotton-like seeds.

The leaves of the Eastern cottonwood.

Immature fruit bunches high up on this particular cottonwood.

It is believed that Native Americans discovered the design for tipis by twisting the leaf of a cottonwood which produced the conical shape. The tree is also a very fast grower, up to six feet per year. (Harlow)

Boxelder – Acer negundo L.

Found in the bottomlands, I assume this area gets regular flooding. My boots got muddy from this spot.

The leaf of the Boxelder is compound, opposite, with anywhere from three to nine leaflets. The leaflets are extremely variable but resemble other maples, hence the alternate name “Ash-leaved Maple.” The fruits are v-shaped and similar to other maples as well.

Leaf of the Boxelder

Shrub-like Boxelder that I happened upon.

Perhaps one of the most widely dstributed maples, Boxelders are very hardy but short lived. Native Americans used its wood for musical instruments. (Harlow, https://www.weekand.com/home-garden/article/boxelder-tree-18037478.php)

Northern Red Oak – Quercus rubra L.

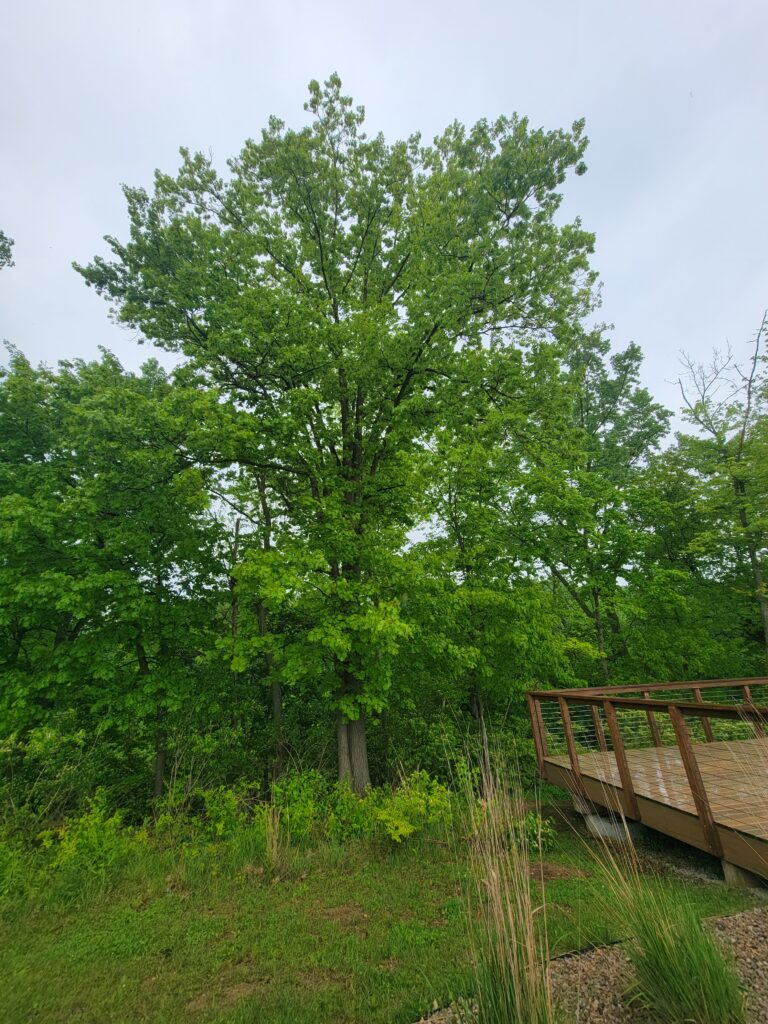

Found near the cottonwood. Forest edge overlooking the Scioto but closer to the riverbank than the cottonwood.

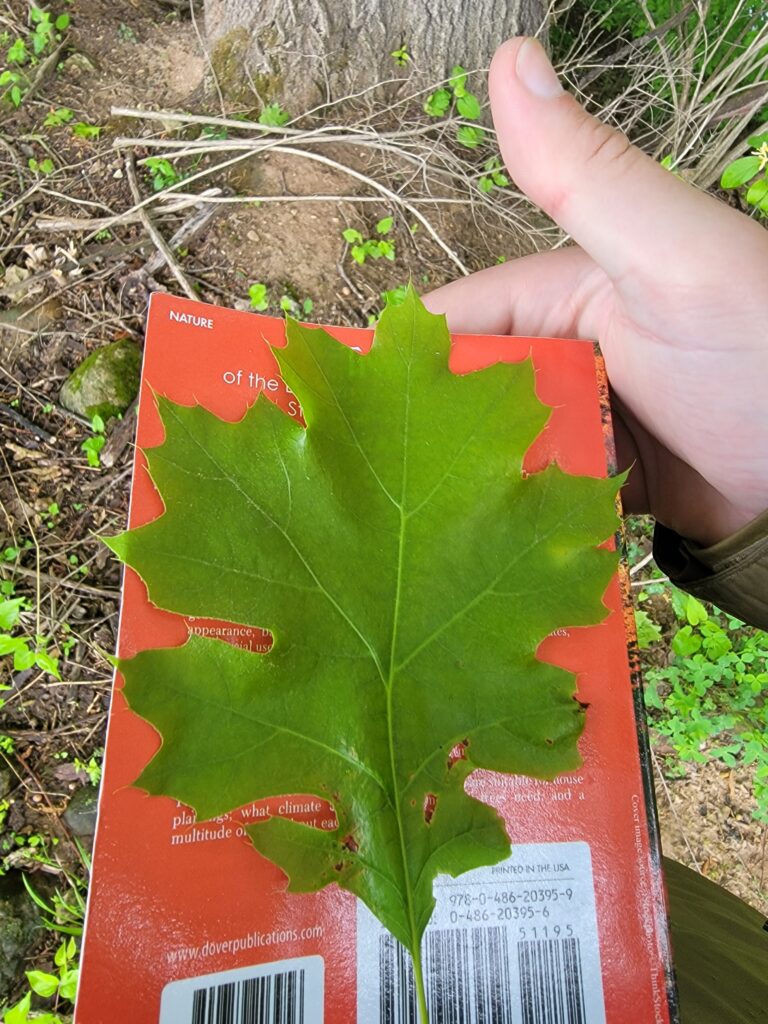

The leaves of the red oak are alternate, simple, oblong or oval, and lobed up to eleven times. Red oak and white oak are easily mistaken, however the leaves of the red oak are bristle-tipped and the acorn has a saucer-shaped hat.

The leaf of the Northern red oak

The might red oak I found while adventuring!

The acorns of the Northern red oak are favored by many wildlife species, especially game animals such as turkeys. (https://mortonarb.org/plant-and-protect/trees-and-plants/northern-red-oak/)

Basswood – Tilia americana L.

Found near the sycamore. Right on the riverbank, which was eroded into a ledge about 10-15 feet above the water.

The leaves of the Basswood are alternate, simple, almost circular with a noticeable uneven heart shape at the base much like a hackberry leaf. Leaves are serrated and usually quite big.

Basswood leaf.

The Basswood tree is perhaps the best source of rope made from a forest source. Native Americans claimed it to be superior to normal rope, as it is softer when wet and doesn’t kink when dry. (Harlow)

American Hornbeam – Carpinus caroliniana Walt.

Found in bottomlands right next to the Boxelder.

The leaves of the American hornbeam are alternate, simple, oval, double-serrated, with distinct parallel veins. Often confused with the leaves of Elms which are more spherical. Tree often takes a shrubby form.

The leaf of American Hornbeam.

Pioneers used the wood of the hornbeam for dishes since it is resistant to cracking. Wood is heavily used by beavers for their shelters. (https://wp.towson.edu/glenarboretum/home/american-hornbean/)